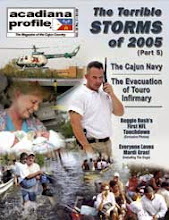

The Story of the Cajun Navy: How Heroic Louisiana Volunteers Saved Thousands of Hurricane Katrina Evacuees

In the hours immediately following Hurricane Katrina’s devastating assault on New Orleans with violent category three winds, unprecedented tidal surges, and lethal floodwaters, millions of Americans watched the alarming scene on television in dismay. This story is about the hundreds of first responder volunteers who could not watch the suffering of their fellow citizens without offering their assistance.

From the last day of the storm on Monday, August 28 to Sunday, September 4, 2005, these south Louisiana citizen volunteers worked tirelessly to save stranded New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish floodwater victims, and brought them safely to dry land. These first responders who brought their boats and risked their lives in the service of stranded flood victims have come to be known as the “Cajun Navy.” Tuesday, August 29, 2005. Surprisingly, the heroic story of Louisiana Senator Nick Gautreaux’s citizen navy volunteers begins at Nash’s Restaurant in Broussard, Louisana.

Tuesday, August 29, 2005. Surprisingly, the heroic story of Louisiana Senator Nick Gautreaux’s citizen navy volunteers begins at Nash’s Restaurant in Broussard, Louisana.

Gautreaux and an associate, Randy Breaux, a Lafayette-based Insurance agent, were planning to have a relaxing lunch at 11:30 a.m. tuesday morning when they both found themselves transfixed by the disturbing images of devastation they were watching on the television; images of flooding on an unprecedented scale in the city of New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish where countless neighborhoods were submerged for miles under as much as 20 feet of Lake Ponchartrain and hurricane storm surge floodwaters.

At Nash’s, television reports were saying that on the previous day, Monday August 28, three critical New Orleans canal levees were breached throughout the early morning hours while Hurricane Katrina was roaring through the city snapping oak trees like twigs, destroying power lines, smashing homes, and tossing enormous sea-going vessels ashore like they were toy boats.

That monday morning the residents of St. Bernard Parish who did not evacuate were overwhelmed by 20 feet of water in less than 20 minutes, knocking out electrical power and pushing raw sewage into the rising tide.

St. Bernard Parish, an area of 680 square miles with a population of 67,000, suffered a one-two punch of raging floodwater from breeched levees in New Orleans and from Hurricane Katrina’s massive storm surge that entered unobstructed through the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO), completely swamping homes and businesses too quickly for many who were unable to react and escape alive.

Most of the dead were elderly or disabled. Some elderly residents were discovered days later still seated in their living rooms. On tuesday morning, live television images showed the sun shining brightly on tranquil floodwaters though a calm, clear sky, revealing an undeniably inundated New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish. Thousands of local residents who stayed behind, either by choice or because of the inability to leave, were now trapped on their rooftops desperate to escape, or had taken shelter in their attic, a dark deadly trap for many who were drowned as the cold, murky surge waters continued to rise rapidly.

On tuesday morning, live television images showed the sun shining brightly on tranquil floodwaters though a calm, clear sky, revealing an undeniably inundated New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish. Thousands of local residents who stayed behind, either by choice or because of the inability to leave, were now trapped on their rooftops desperate to escape, or had taken shelter in their attic, a dark deadly trap for many who were drowned as the cold, murky surge waters continued to rise rapidly.

While watching the shocking images of devastation and desperate people on television at Nash’s, Gautreaux announced to his friend, “I have to do something to help those people. We can’t just stand around and watch those people on their rooftops.”

Gautreaux told his friend what he wanted to do: organize a volunteer citizen flotilla of hundreds of boats with hundreds of volunteers and drive to New Orleans to rescue people trapped on their roofs.

According to Gautreaux, “I told Randy what I wanted to do and he said to me ‘are you crazy?’ I said to him, we’re going to get it together. Watch what happens. Randy ended up coming with me.”

Gautreaux recently explained his motivation to organize a citizen flotilla. As the father of three young daughters, and a wife six months pregnant on that fateful tuesday afternoon, Gautreaux said he would want someone to be there for his family if such a catastrophe happened to his pregnant wife and children.

While driving to his District 26 office in Abbeville, with his extraordinary plan firmly in mind, Gautreaux telephoned his office assistants to say alert the local news media and tell them what I want to do.

On his way to Abbeville, Gautreaux sent a text message on his Blackberry to Louisiana State Senator Walter Boasso, a lifelong resident of St. Bernard Parish, to get the latest news about how things were going in that parish, and to ask what could he do to help. Attempts to telephone Boasso by cell phone were unsuccessful.

Boasso, who had been rescuing people from rooftops in St. Bernard since late monday afternoon, replied with a short chilling text message Gautreaux says he will never forget: “my people are dying. please send help.” Gautreaux sent back his reply, “don’t worry. help is on the way.”

That tuesday afternoon during the five-o-clock television news on Lafayette’s KATC and KLFY, Gautreaux’s request for citizen volunteers with boats was broadcast throughout Acadiana. Gautreaux’s news announcement was simple: ask every able-bodied citizen with a boat to show up at the Acadiana Mall on Johnston Street in Lafayette, Louisiana by 5 a.m. wednesday morning and drive to New Orleans to help rescue stranded flood victims.

Today Gautreaux says, “I appealed to the people of Acadiana. I said meet us at Acadiana Mall at five-o-clock, and here’s the number to my office. Within about an hour we received over 200 phone calls.”

When Gautreaux arrived at the Acadiana Mall in the early hours of wednesday morning he was stunned by what he saw. The Mall parking lot was filled with boats and trucks of all shapes and sizes and hundreds of people willing to help rescue their fellow Louisiana citizens.

“The great thing about it was it was typical Louisiana,” says Gautreaux. “We had doctors, lawyers, college students, nurses, working class people, and offshore oilfield workers who had the day off because of the hurricane. We even had a person who bought a brand new boat and motor that day so he could go with us. I thought that was great. It’s part of our Cajun heritage to help our neighbor. When New Orleans needed help we were there to help them.”

Participants in Gautreaux’s citizen flotilla came from all around South Louisiana: Ville Platte, Lake Charles, Abbeville, Erath, New Iberia, Maurice, Carencro, Jennings, and Opelousas, just to name a few. Eyewitness estimates put the number of boats between 300 and 500, and the number of volunteers at 600 to 800. By all accounts, hundreds of volunteers showed up to help with hundreds of boats.

Although Gautreaux was quite pleased with the turn out, he had a stern warning to deliver to his enthusiastic volunteers who were eager to get going. Standing next to a Vermilion Parish sheriff department squad car with a bullhorn in hand Gautreaux had this to say to the volunteers, “This is the deal. If you’re afraid to see death, don’t come. If you’re afraid to see a dead body floating in the water, don’t come. If you’re afraid to be shot at, don’t come. If you’re not used to the smell of death, don’t come with us.”

Recalling the scene Gautreaux says, “I warned them. And not one person turned around to leave.”

At 4:30 a.m., Wednesday, August 30, Gautreaux’s plan entered phase two as hundreds of boat owners left the Acadiana Mall traveling at top speed down I-10 with a police escort, rapidly making their way to New Orleans toward a life altering experience that would bring them face-to-face with human suffering on an unimaginable scale.

The Humanitarian Disaster Begins

Monday, August 28, 2005. During the morning hours of August 28, while Katrina continued to pound New Orleans, reports of breeched levees and wide spread flooding were pouring into the State of Louisiana Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP) in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

While monitoring the storm at the OEP, Senator Walter Boasso was approached by Captain Brian Clark, the Region 8 Supervisor of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Enforcement (DWFE), who told Boasso he and DWFE Lt. Col. Keith LaCaze were organizing a search and rescue mission of 100 DWFE agents with 60 boats, and Clark wanted to know if the senator would come with them. Boasso agreed to join their mission.

Arriving at the junction of I-10 and Causeway Blvd at 2 p.m., Boasso and the DWFE detail could go no farther south on I-10 due to deep floodwaters that stretched as far as they could see. Boasso’s plan was to try and reach the St. Claude Avenue Bridge and get into St. Bernard Parish to survey the damage and rescue any survivors they may encounter.

After a few hours of searching for a safe route, eventually Boasso reached the bridge at St. Claude, but could go no farther. The floodwater had risen so high the bridge itself was barely above water. Boasso’s plan was to travel to the Jackson Barracks, a half a mile away, where the National Guard was stationed and the DWFE kept some of their boats. When Boasso’s detail arrived at St. Claude Bridge they had only 20 boats, as other agents had earlier split up to reconnaissance throughout the flood zone.

The DWFE agents with Boasso launched their boats off of the side of St. Claude Bridge, and as soon as the boat motors were turned on, Boasso heard the forceful voices of desperate people coming from every direction begging for help.

As their train of boats slowly motored forward down St. Claude Avenue Boasso recalls, “We didn’t make it a block and I told Brian Clark, let’s turn these boats loose. So we turned everybody loose and told them to go rescue everybody you can rescue. Brian and myself and another agent continued down St. Claude Avenue in our boat and the people were screaming and hollering for help and shooting flare guns, and saying please come and get us, waving towels, hoping we would shine our flashlight on them. All I could tell them again and again, we’ll be back at daylight to get you. We’ll be back at daylight to get you. And this went on block after block.”

As night fell, the first dark night of the Great Deluge began.

Boasso recalls, “It was as black as can be. The only lights we had were the broken gas mains that were leaking and had caught on fire. The fires were on top of the water. And the water was still rising. There was no electricity. The city power was out. Dangerous debris was all around us and under the water, like cars and dumpsters. Power lines were down all around us, and floating in the water. You had to move your head to the side to dodge traffic lights and fallen trees. It was slow going.”

Traveling deeper into St. Bernard, Clark would occasionally turn off the motor of their boat, and the three men could hear desperate cries for help emerging from the pitch-black darkness in all directions.

Boasso’s cell phone wouldn’t work, so he sent urgent text messages on his Blackberry pleading for help to every friend and associate he could think of throughout the macabre evening’s reconnaissance mission activities that took him all the way to Chalmette. And at some point during the evening Boasso realized his own home was lost underneath the floodwaters. Although his family had evacuated and were safe, his most prized family possessions were destroyed and gone forever. Clark, also a St. Bernard native, had suffered the same fate.

But Boasso and Clark also knew they had a duty to perform for the people of St. Bernard Parish who needed to be rescued and evacuated to dry land. Boasso had a master plan in mind. On tuesday morning, August 29, after a long sleepless night, Boasso and Clark aggressively went in search of volunteers to help them build what would come to be known as Camp Katrina (photo), a massive warehouse near the Mississippi River on Chalmette Slip Road that could shelter thousands of evacuees, house tons of emergency supplies, and offer an escape route by ferry across the Mississippi River to dry land at Algiers Point. Flood victims scattered throughout the parish could now be brought to one place and quickly evacuated to safety.

On tuesday morning, August 29, after a long sleepless night, Boasso and Clark aggressively went in search of volunteers to help them build what would come to be known as Camp Katrina (photo), a massive warehouse near the Mississippi River on Chalmette Slip Road that could shelter thousands of evacuees, house tons of emergency supplies, and offer an escape route by ferry across the Mississippi River to dry land at Algiers Point. Flood victims scattered throughout the parish could now be brought to one place and quickly evacuated to safety.

Clark recruited volunteers at a local high school where stranded citizens were crowded on the school’s flat, second story roof, and Boasso found more volunteers at a nearby prison that was surrounded by dry land. The work would be done in sweltering south Louisiana heat, with no cool water or tasty food to enjoy during work breaks. Their clean up labors took four hours to complete.

While clearing the Camp Katrina warehouse of debris and scores of stacked plywood on pallets with forklifts and muscle, Boasso received a text message from his friend and fellow senator, Nick Gautreaux, who was inquiring about the situation in St. Bernard. Boasso sent back his chilling reply…my people are dying, send help.

The rescued flood survivors that were evacuated to safety from Camp Katrina came from every social background and status; doctors, lawyers, waitresses, janitors, teachers, nurses, wealthy and poor.

Since Boasso’s cell phone rarely worked, he was forced to send text messages with his handheld Blackberry to enlist fellow Louisiana government officials to make things happen quickly.

Boasso enlisted the help of Ty Bromell, the director of rule development at the State of Louisiana Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP), who recruited buses, drivers and supplies such as ice, water, diapers, generators, medicine, chain saws, and body bags. Buses took evacuees at Algiers point to Kenner Airport and Belle Chaise Airport.

Literally thousands of volunteers donated supplies through Bromell’s OEP donation hotline, such as the Salvation Army and various non-profit organizations, and hundreds more recruited volunteers helped deliver the supplies.

Louisiana Senator Rob Marianneaux recruited ferries, a barge, and a tugboat, donated by Angus Cooper of Osprey Lines, to move large amounts of supplies downriver from the Port of Greater Baton Rouge in Port Allen to both New Orleans and Camp Katrina.

Boasso also received help from Sam Jones, the governor’s liaison to parochial and municipal government, who recruited buses, 18 wheel trucks, and the Lake Charles area Cajun Navy volunteers who helped rescue hundreds of residents in St. Bernard Parish and New Orleans.

Gautreaux’s Citizen Flotilla Arrives in New Orleans

Wednesday, August 30, 2005. Early Wednesday morning at 6:00 a.m. Gautreaux and his citizen flotilla volunteers arrived in New Orleans and rendezvoused with Captain Clark and his Wildlife and Fisheries agents who had set up headquarters at the Clearview Shopping Center at the junction of Clearview Parkway and I-10.

According to Gautreaux the DWFE agents were overwhelmed by the huge number of Cajun Navy volunteers, a long line of trucks and boats of all shapes and sizes stretched for miles like a cargo train along I-10. “We thought we could just go there and start launching boats. But we had to wait. What people didn’t understand was that, where they wanted to launch, they would have returned to find their cars underwater. The water was still rising. We brought so many people they were overwhelmed.”

Although hundreds of volunteer’s boats eventually received search and rescue assignments that morning from the DWFE and taken to critical areas throughout the flood zone of New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish through circuitous and hazardous routes, some volunteers were turned away because their houseboats, party barges, and deep draft boats were too big or unsafe for a rescue mission. And some volunteers simply waited so long to get an assignment they decided to go back home.

Ryan Mathers, a citizen flotilla volunteer from Maurice, Louisiana recalled, “We sat and waited for about four hours.”

Mathers borrowed a boat to participate in the search and rescue mission; a 14-foot, flat bottom boat that could seat 6 passengers. He waited patiently in his truck with his fellow volunteer, Aaron Hoffpauir, from Erath, Louisiana, hoping to get an assignment from the DWFE.

Finally, Mathers decided get out of his vehicle to go in search of a DWFE agent who would give him a mission, and his initiative was soon rewarded. Mathers was directed by a DWFE agent to follow him and a group of 15 Cajun Navy volunteer boats to various staging areas throughout the 9th Ward. Mathers brought his rescued passengers to a nearby Texaco gas station where DWFE agents would load the evacuees on buses.

Another citizen flotilla volunteer, Deacon Don Leger of St. Barnabas Episcopal Church in Lafayette, Louisiana, embarked on quite a different route than Mathers to find a search and rescue assignment. In the chaotic whirlwind of strategic confusion that was New Orleans on Wednesday morning, those volunteers who were the most persistent eventually were given a mission.

In Deacon Leger’s case, his group of volunteers grew tired of waiting on I-10, and they decided to find a way in to the city on their own. The route they chose took them south on Causeway Blvd to the Huey P. Long Bridge, crossing the Mississippi River into Westwego, then driving south to the Crescent City Connection bridge, and back across the Mississippi River, then down into New Orleans where their group was diverted by police, passing by the Convention Center to Harrah’s at Canal Street.

When Leger’s group arrived at Harrah’s they were told by a Louisiana State Police officer, “We don’t need you.” Hearing this news, some volunteers turned around and left. But Leger and those who stayed were adamant about finding a mission.

Eventually they found a sympathetic City of New Orleans police officer who guided Leger and 40 boat owners across the breeched Industrial Canal levee into St. Bernard Parish where they launched their boats on I-10 just north of Chef Menteur Highway.

Before their citizen flotilla launched, the police gave the crew a few helpful warnings about what they would see out there in no man’s land. “The police said go right out there and you will hear people, you’ll see,” says Leger. “He said watch for any movement because some people are in the attic with attic vents and they’ll drop a white cloth or napkin through the vent, so be observant.”

At Leger’s first stop, he was forced to get waist-deep into the putrid smelling, murky floodwaters. Months later he was still nursing chemical burns on his legs he developed from wading in the contaminated water that was fouled with household chemicals, poisons and raw sewage.

Leger’s impression of the survivors he was saving was one of extreme despair. “People seemed to be in a state of shock and bewilderment. They thought it was only their neighborhood that flooded. But after riding in the boat for a couple of miles, as far as they could see, they saw devastation. Many had nothing more than a brown paper bag that held what was left of their worldly possessions. People had a forlorn look in their eyes, knowing they’d lost everything.”

Throughout the day Leger and his fellow crewman lifted wheelchair-bound elderly survivors into their boat, and turned away flood victims swimming in the polluted brown water who tried to cling desperately to their small, over-crowded craft begging them with pleas of “one more, please, one more.”

Leger’s memories of that day also includes the sight of numerous floating dead animals, swimming snakes, rats, and rabid dogs who had to be pushed away from their boat with an oar.

Toward the end of that hot, tiring wednesday, Leger recalls floating slowly past an apartment complex where a huge black Labrador retriever was looking out of a second story window at their passing boat. Leger says, “That dog went to the back of the room, and then came running and leaped through the glass window to get out of the apartment.”

While this amazing animal swam toward their boat Leger’s fellow crewman told him, “This dog wants to be saved.” When the paddling Lab finally arrived at the side of their boat, the two men hauled the enterprising dog out of the water and gave him a ride to safety.

Even though Leger was told by the New Orleans police to leave pets behind, in defiance he saved a little boy’s pet parakeet that was given to him on monday, August 28 as a birthday present. And he rescued an elderly woman’s newborn puppy by putting it in a shoebox he found at the top of her bedroom closet, and poked air holes into the shoebox cover so the puppy could breathe.

Although Leger was also told to leave dead bodies behind and concentrate on rescuing the living, as an ordained deacon he felt a responsibility to stop a moment and say a prayer for the family of the dead bodies they encountered. According to Leger, “One of the things that distinguishes humans from all other animals is that we care for our dead. When you get to a point where there is no time to honor your customs and traditions, that’s a sign the world has been turned upside down.”

At the end of his day with the sunshine rapidly disappearing, Leger decided to hitchhike home to Lafayette, and as soon as he held out his thumb for a ride, a car driven by an LSU student stopped to give the white-collared deacon a lift to Baton Rouge where he phoned his wife to ask her to come and get him, and to “please bring me some dry clothes.”

Wednesday, August, 30, 2005. Just a few blocks away from Deacon Don Leger’s rescue operation that very same wednesday, the storied Cajun Navy volunteers from Lake Charles described in the bestseller, “The Great Deluge,” by Douglas Brinkley, were also hard at work rescuing elderly patients, residents and their pets near the Crystal Palace on Chef Menteur Highway in St. Bernard Parish.

By noon on Wednesday their 34 member, 17-boat citizen flotilla had rescued close to 1000 people from Forest Towers East Apartments, an apartment tower for senior citizen residents on Lake Forest Boulevard, and the Metropolitan Hospice for senior citizen patients on Read Boulevard, plus stranded private home owners trapped by the flood. And they continued their rescue efforts well into the following Sunday afternoon.

The Lake Charles citizen flotilla odyssey began early Tuesday morning at 6:30 a.m. when Ronnie Lovett, owner of R & R Construction in Sulphur, Louisiana, telephoned his friend and New Orleans native, Andy Buisson, to suggest they should get together to help rescue the flood victims they were watching on television that morning. Buisson told Lovett he was already thinking the same thing.

An early riser and former Navy 2nd Class Petty Officer, Lovett’s instinct for volunteerism kicked in after he awoke at 3:00 a.m. and turned on his television to see and hear about the potential humanitarian disaster developing in Louisiana’s Crescent City. Levees had been breached, and thousands were stranded in the flood. Lovett had also helped to assist the victims of Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and has been a public service volunteer continuously throughout his adult life. “That’s what I do,” says Lovett today.

Not long after Lovett spoke to Buisson about the idea of doing something to help, he received a phone call from Buisson’s wife, Sara Roberts, a certified public accountant in Lake Charles and member of the Superdome Commission, who said she had just received a call from Sam Jones, the governor’s liaison to parochial and municipal government, who asked her if she could help find volunteers with boats to rescue stranded flood victims in New Orleans. Jones told Roberts her citizen flotilla volunteers could meet up with Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Enforcement (DWFE) agents in New Orleans at Causeway Boulevard and I-10.

According to Lovett, “That gave us a plan and way in.” Hearing this encouraging news, Lovett immediately set about building his navy.

With 600 R & R Construction employees to ask for assistance, Lovett promised everyone he contacted hourly wages 24/7 for all volunteers. “Nobody turned me down,” says Lovett. He eventually hand picked only boat owners and experienced boatmen for the mission, and brought along a tool truck and a fuel truck.

After Lovett’s navy was quickly cobbled together, he had assembled a crew of 17 boats and 34 boatmen employees from the Lake Charles area and from as far away as Lake Arthur, Ville Platte, and Opelousas, plus the boat and supplies of Buisson and Roberts who lead the navy caravan from Wal-Mart in Jennings toward their New Orleans rendezvous with Wildlife and Fisheries agents.

When the Cajun Navy arrived in New Orleans tuesday at their designated launch point at Causeway Boulevard and I-10, they were redirected to Sam’s Club on Airline Drive, then to Harrah’s Casino on Canal Street where they spent the night in sleeping bags on the side of the road, not far from the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center on Convention Center Boulevard where a huge crowd of hurricane refugees were gathering, expecting to be evacuated soon.

At daybreak wednesday morning, the Lake Charles citizen navy was escorted by New Orleans police officers to the Crystal Palace on Chef Menteur Highway where they would launch their storied vessels and begin rescue operations of stranded and helpless deluge refugees.

By 2 a.m. thursday morning the entire flotilla crew had come to agreement that they should return to Lake Charles to replenish their food and water supplies, which they gave away to the people they rescued.

Early friday morning Lovett’s navy went back to New Orleans to help. Only this time they brought 35 boats and even more boatmen. Buisson returned with the new crew, but Roberts had fallen ill on wednesday evening, and could not participate in the mission.

That friday morning Lovett’s replenished crew drove to New Orleans arriving from the west bank of the Mississippi River in Gretna, Louisiana anticipating their return to Forest Towers East Apartments and Metropolitan Hospice, where they promised patients and residents they would return to rescue them. Their promises were thwarted wednesday evening when the crew was forced to leave due to their unanticipated exhausted supplies, and the new intimidating threat of deadly violence throughout the city that was being reported by the police.

When Lovett’s flotilla arrived in Gretna, Louisiana friday morning they were asked by the Sheriff’s department to help transport water and emergency supplies from New Orleans across the Mississippi River into Gretna at the Jackson Avenue Gretna Ferry landing, and Lovett’s crew complied with the request.

Then, after having accomplished that task, Lovett’s construction employees were asked to clear trees and debris from strategic Gretna area roads with bulldozers. These transport and clearing efforts took all day friday to accomplish, forcing Lovett’s crew to bed down inside their trucks at Harrah’s Casino friday evening before resuming their promised rescue efforts at Forest Towers and Metropolitan Hospice.

At dawn Saturday morning Lovett’s citizen flotilla returned to Forest Towers East Apartments to continue their rescue efforts. They were surprised to discover the residents they had to leave behind wednesday evening had yet to be evacuated. This saturday’s rescue operation would take half a day to accomplish.

On Sunday Lovett’s crew returned to Metropolitan Hospice and once again found familiar faces were still there and clinging to life. One particular hospice resident was an African-American chaplain who would not leave wednesday evening with Lovett’s crew without also bringing the six elderly bed-ridden white female patients he was looking after at the hospice. On sunday afternoon when the Cajun Navy returned, the chaplain was still there, but only two of the women were still alive.

Before the chaplain would allow the Cajun Navy to take his two remaining patients, Lovett had to guaranty the women would not be stranded on the side of the road, waiting for hours in the hot sun for evacuation from the Crystal Palace staging area where a large crowd still remained.

So, with this task in mind Lovett returned to Crystal Palace with a boatload of evacuees, thinking of a way to evacuate the chaplain’s patients. After he arrived, as luck would have it, he saw a Navy truck traveling toward him on Chef Menteur Highway. Lovett waved his arms and flagged down the military vehicle. After the Navy personnel listened to his story about the chaplain and his two patients, the driver agreed to wait at Crystal Palace for Lovett to return with the chaplain and the women, who would be taken to a medical facility in Baton Rouge. The chaplain was later given a ride to Baton Rouge for medical care by none other than Sam Jones, the Cajun Navy recruiter.

That sunday afternoon, when rescue operations were winding down, the New Orleans police told Lovett they were looking for volunteers to help remove corpses from the floodwaters. When he heard that news, Lovett says he turned to his hard working construction company employees and told them, “Fellas, it’s time to go home.” So they packed up their gear, their tools and supplies, and hitched up their boats to their trucks, and left New Orleans having saved hundreds of lives. Little did the Cajun Navy know that their selfless volunteerism would eventually become legendary; one of the few bright lights in a dark, sad tale.

Origins of the Name “Cajun Navy”

When Douglas Brinkley, author of “The Great Deluge,” was traveling throughout New Orleans immediately after the hurricane and taking notes for what would become his future bestseller, he made his way to Harrah’s Casino on tuesday afternoon and noticed a line of boats owned by private citizens who did not appear to have any government affiliation. Brinkley asked a New Orleans police officer, “Who are those people with the boats?” The officer looked at the boats, then smiled and said to Brinkley, “That’s the Cajun Navy.”

Today, Brinkley says when he began to write his book, in the notes he took that day he had also written the term “The People’s Navy.” Brinkley says he chose the use Cajun Navy in his book because, “It sounded more regional and would give credit to all the south Louisiana volunteers.”

In subsequent interviews since the publication of his book, Brinkley has referred often to all of the south Louisiana citizen flotilla volunteers collectively as the Cajun Navy.

Another source for the name Cajun Navy comes from Deacon Don Leger, who says that when he arrived at the Acadiana Mall in Lafayette to join Senator Gautreaux’s citizen navy, he was walking among the volunteers who had gathered there, looking for a familiar face. While wandering through the crowd Leger says he noticed a white ice chest sitting on the seat of a boat that had the words “Cajun Navy” written in black magic marker on the side of the ice chest.

Perhaps the use of the name Cajun Navy to describe hundreds of south Louisiana residents with boats was simply inevitable.

Gautreaux’s Tireless Rescue Efforts

On one of Gautreaux’s memorable missions, and there were many, he came across a family marooned on their rooftop with an elderly woman in their group who recently had surgery. The family told Gautreaux to help other victims first, and then come back later that afternoon. They assured him their elderly family member would be okay. Today Gautreaux deeply regrets leaving the woman behind. He promised her he would come back.

Before he could come back to bring her to safety his afternoon became unexpectedly busy when he came across 175 people stranded on a shrimp boat floating aimlessly toward the Gulf of Mexico in Violet, Louisiana. The boat was filled with nurses and a few pregnant women who had evacuated from Chalmette Medical Center, miles north of Violet. Their rescue took all afternoon and well into the evening; too late and dark to find the elderly woman and her family. But the nurses were saved, and the pregnancies were successful.

The next morning, the DWFE detail that was sent to rescue the woman and her family reported to Gautreaux the elderly woman died in their boat on the way to safety. To this day tears still well up in the senator’s eyes when he tells this story about the woman he says he should have saved when he had the chance. He promised her he would come back that afternoon.

Throughout the week Cajun Navy volunteers saved hundreds of lives in New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish, risking their lives to save their fellow citizens, experiencing a humbling, life altering view of humanity overcome by grief and despair. For some volunteers, the tragedy they witnessed in New Orleans is still difficult to recount without being overcome by silencing tears.

New Orleans – "A Changed Place Forever"

A lifelong native of St. Bernard Parish, DWFE agent Captain Brian Clark, worked tirelessly to rescue his neighbors knowing that his own home, and all of his worldly possessions, had been swept away by the great deluge. But Clark soldiered on, pushing aside that day of reckoning when he and his evacuated family would have to face the magnitude of their losses.

Today Clark remembers how he managed to hold himself together and not give in to despair. “I guess it’s a sense of mission,” he says, “a sense of service. You feel like it’s your responsibility to take care of others. You throw everything on the side and focus on the mission.”

“I’ll never forget this little boy,” says Clark. “It was getting dark. He was with his parents. They were getting ready to get out of New Orleans, and this little boy walked over to me and gave me a piece of cake. I thanked him, and I gave his cake back. I told him, ‘hold on to this, you’re going to need it.’”

“I believe the spirit of the people here will make New Orleans come back,” says Clark. “It’s going to take a long time. But New Orleans will never be the same way it was. This will be a changed place forever.”

Labels: cajun navy, camp katrina, douglas brinkley, hurricane katrina, nick gautreaux, sara roberts, the great deluge, walter boasso